Blogger: Anja Johansen,

Blogger: Anja Johansen,

PhD candidate at Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture, NTNU

Artists in the 15th century had to dissect dead people in the hidden in order to study the inside of the human body. Today the inside of the human body seems to be more available than ever – visually, at least. Imaging technologies such as microscopy, x-ray, ultrasound, endoscopy and MRI have become crucial tools within the biosciences and in medical practice, making new entities and phenomena visible to the human eye. These technologies open up for examining and treating the body in novel ways, which again imply changing ideas about, diseases, health, gender differences, ageing and personality.

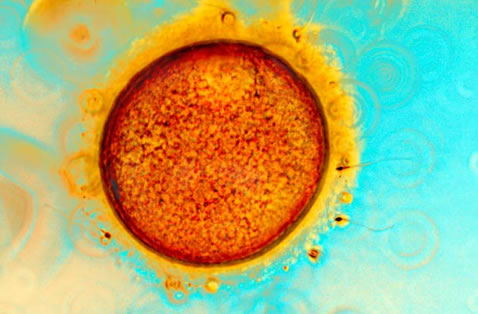

LIFE: The egg cell with sperm – portrait and symbol of life. IVF. (Photo: Spike Walker/Wellcome Images)

Due to new possibilities of digital manipulation, storing and distribution, colourful images of inner organs, cells and the human DNA are not only of interest to scientists and clinicians, but have become part of our daily visual culture. Pictures taken of tiny body fragments are modified into astonishing and aesthetically appealing images used in the media and in commercials, as well as by artists – especially within the growing field of bioart.

The research project Inside out. New images and Imaginations of the body, which I’m a part of, is an interdisciplinary project that studies cultural aspects of medical images from inside the body.

Within the field of Science and Technology Studies (STS), in which this project is situated, we are especially interested in the interface of science, society and culture. In our project we have studied this traffic between science and culture at different sites: In research laboratories, in medical practice and fertility clinics, as well as in science and art museums.

Some of the key questions in this project have been:

- In what ways do new visualisation technologies contribute to changing images and imaginations of the body?

- How do cultural values contribute in the process of producing, interpreting and using these images – not only among lay people, but also in scientific and clinical contexts?

We recently made a short film based on the project, where we interviewed scientists and clinicians, as well as museum curators and science communicators, from Norway and the UK. “The good, the true, and the beautiful” is a film about the cultural aspects of medical imaging, produced in collaboration with Anwar Saab/1001 Films. The film had its premiere in September 2012, and have since been screened at the Norwegian Museum of Science, Technology and Medicine in Oslo, at various conferences within the field of STS, and used in education of students in media and cultural studies.

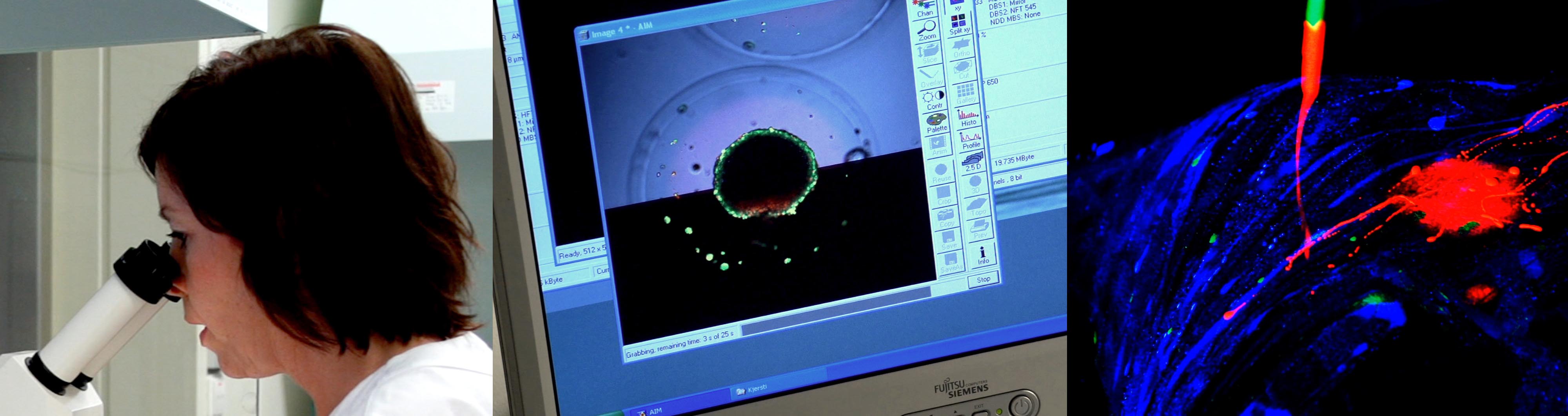

LABORATORY IMAGING: Stills from the film with screen shots from the fertility clinic at St.Olavs and at an imaging lab, as well as artistic interpretation. (Photo: Anwar Saab/1001) Films.

Biomedical research and skilled visions

Fieldwork in an imaging laboratory, undertaken by post doc Manuela Perrotta, has given us a deeper understanding about how cell images are produced, used and interpreted by biomedical researchers. Even though images of cells may look like a snapshot from inside the body, they are nothing like it. To produce them you have to undergo a long process of preparation, selection and postproduction.

Perrotta also investigated how students within the field develop a professional vision. How do novices learn to look for the right things? How do they learn to distinguish when elements in an image are due to changes in the tissue sample, or to an artefact in the microscope? Perrotta analysed how students learn to see and how their abilities to interpret the images are grounded in the whole process of technoscientific imaging.

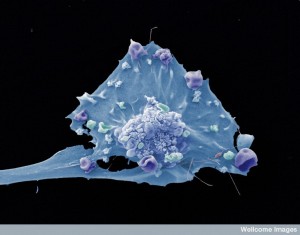

Portraits of cells

In a recently published article about science communication of assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) Merete Lie argues that images of egg and sperm cells represent cells as autonomous and independent of human gendered bodies (Lie 2012). In a similar way as with Lennart Nilsson’s photographs of embryos in the 1960’s, cells become visually – and also conceptually – separated from the body. The cells appear as detachable, usable entities.

In both cases the biological material is also physically detached from the body; as Nilssons photographs were of aborted foetuses outside the womb, not living ones. Adding to the notion of individualised entities, cell images lean on the genre of the portrait, presenting colourful, individualised cells with sharp outlines and fine details towards a dark background. One may ask if the cell has taken over as the personification of life, whereas the human being is increasingly depicted as an environment for the life and growth of cells?

Art and science

Collaboration between art and science is a growing trend for science museums, and the focus of my PhD project. The hope seems to be that artist can provide new methods for communicating scientific knowledge about the body, as well as challenge the existing knowledge with novel perspectives.

One of my cases is an exhibition focusing on the cultural history of the brain and neuroscience, namely Mind gap, exhibited at The Norwegian Museum of Technology, Science and Medicine in Oslo (2010-2012). The exhibition was designed by the artist Robert Wilson, and won an international award for its untraditional design.

As part of the research I visited the exhibition several times, interviewed the museum staff, and watched other people’s reactions during their explorations in the exhibition space. Some seemed to be thrilled about the fascinating objects and mysterious atmosphere, while others were disappointed about the lack of textual information and “hard facts”.

Wanting to evoke curiosity and wonder about the brain and neuroscience, the curators tried to engage the visitor through surprising encounters and multisensorial experiences. Neuroscience has, after all, told us that we learn with our whole body, not only our brains

Facts

- The research project Inside out. New images and Imaginations of the body is led by professor Merete Lie at the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at NTNU. Other participants include Post doc Manuela Perrotta and PhD student Anja Johansen.

- The project is funded by the KULVER programme, the Norwegian Research Council.

- Kjartan Wøllo Egeberg, Senior Engineer at the Department of Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine and Arne Sunde, leader of the Feritilty Clinic at St.Olavs Hospital, are among our collaborators in the medical field.

- We are also collaborating with senior curator Henrik Treimo at the Norwegian Museum of Science, Technology and Medicine, who was responsible for the production of Mind gap.

- “The good, the true and the beautiful”, a short film about cultural aspects of medical images was produced as part of our research project, in collaboration with Anwar Saab/1001 Films. Teaser available here: http://www.ntnu.no/kult/insideout