Blogger: Jane Atesoh Awuh, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine and Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (SFF-CEMIR).

Most often we become passionate and involved in issues in this life for very personal reasons. I am particularly drawn to infectious diseases because I hail from a society that is plagued by one kind of infection or the other. If you are not killed by one infectious disease you will be by the other, and if not by disease, it will be by war or hunger. I know two relatives who died of tuberculosis, one of them only a couple of months ago. Tuberculosis (TB) is still a disease of poverty although there is increasing incidence even in developed countries. HIV and TB are a dangerous liaison wherein HIV infects and destroys the very cells that should protect us from TB. These diseases are still considered shameful and surrounded by stigma.

To survive TB, support from family, friends and communities is as important as medication. TB can be treated through a long course of several antibiotics, over a minimum of six months. The medications might make you more sick, but if taken regularly, you will be completely well again. Six months is a short time compared to an entire life time, although many still fail to take their medication regularly. Even more fail to get treatment at all, because they are used to being poor and ill, and do not seek help in time.

Thanks to the amazing work of basic scientists around the world, there is always a little light at the end of the tunnel. The work of basic scientists is often the foundation of whatever treatment and prevention strategies that eventually end up at the bedside of patients. And the steps to arriving at the very first clinical trial is often accompanied by a succession of failures, hopelessness and sleepless nights. Yet they are not always given enough credits and funding. The causal agents of mycobacterial diseases are an intriguing group of microorganisms that continue to baffle these brilliant minds around the world even when we think we have got it all figured out. Of these, Mycobacterium tuberculosis which causes tuberculosis is one force to reckon with especially in individuals who are immunocompromised for one reason or the other. Another one of these bugs causes leprosy and indeed the Norwegian scientist G. H. Armauer Hansen in 1873 discovered the bug, making it the first bacterium to be identified to cause disease in humans and since then pioneered research in leprosy. It’s amazing that these infections have been with us for thousands of years yet we are still struggling to keep it in check. How can a single-celled organism like these be so complex that they cannot be untangled by even the most brilliant minds in the field?

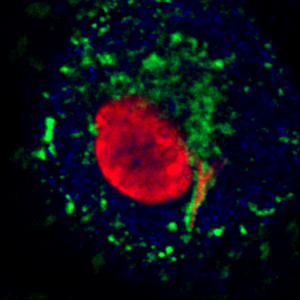

Confocal image of mycobacteria (red rods) within a macrophage coated with LAMP1. Photo: Alexandre Gidon

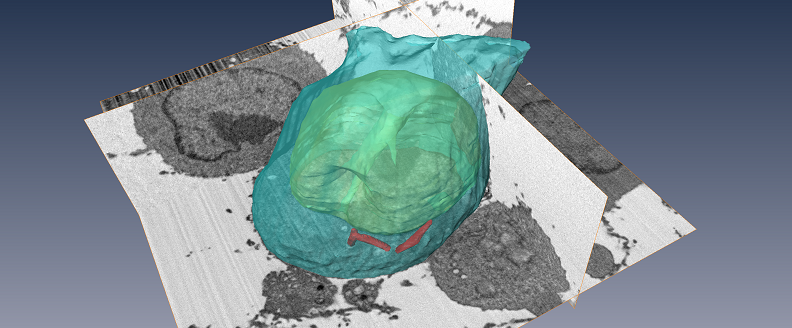

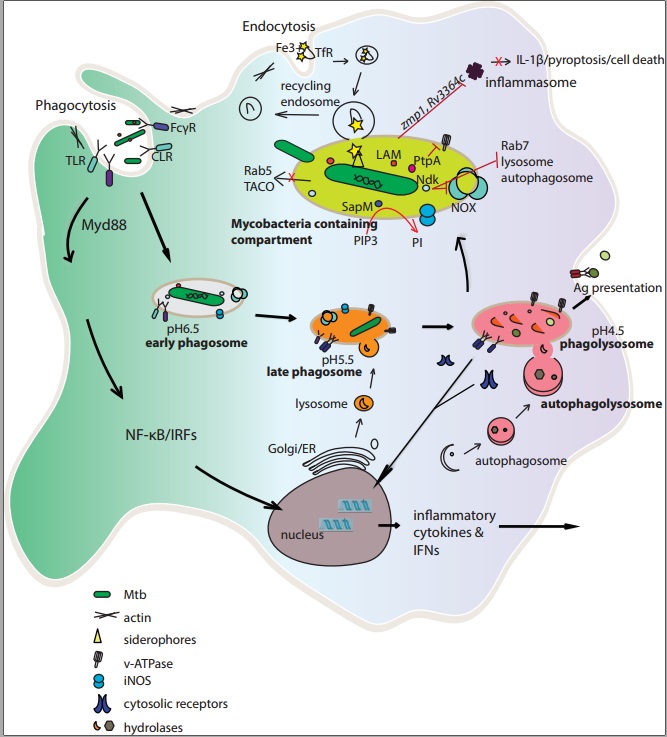

Approaching the end of the year could not be a better time to summarize current research findings in the world of these creepy, invisible creatures. In a recent issue of the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, we summarize the current standing on how these bugs have managed to stay with mankind for so long and I have a feeling we are still only scratching the surface of this enigma. To add to the whole complexity is the fact that these bugs actually prefer and thrive in one of the deadliest immune cells known – the macrophage, as a natural habitat. How can that be?

Macrophages play an essential role in the immune system by ingesting and degrading invading pathogens, initiating an inflammatory response and instructing adaptive immune cells, and resolving inflammation to restore homeostasis. We summarize mechanisms by which intracellular pathogens, with an emphasis on mycobacteria, manipulate macrophage functions to circumvent killing and live inside these cells even under considerable immunological pressure. Remember the good news; these infections are treatable although rise in drug resistance continues to be a challenge as with all other infectious diseases. A clear understanding of host responses elicited by a specific pathogen and strategies employed by the microbe to evade or exploit these is of significant importance for the development of effective vaccines and targeted immunotherapy against persistent intracellular infections like tuberculosis. Read more here.