Blog by: Mattijs Elschot

Postdoctoral Fellow at MR Cancer Group

Some prostate cancer patients need radical surgery to survive, whereas others can do without any form of treatment. The urologist determines to which group a patient belongs. Researchers at NTNU/St. Olavs Hospital investigate whether a PET/MRI scan can help making the correct decision.

Trondheim is proudly home to the only officially registered moustache club in Norway, thus making it the facial hair capital of the country. Stroll around the city center for a couple of hours and you shouldn’t be surprised to come across a fancy moustache or two. In November, the odds of spotting mustachioed men are even higher than usual, as many are joining Movember’s shaggy campaign to raise funds and awareness for men’s health.

Prostate cancer constitutes a significant burden to men’s health in Norway, with almost 5000 new cases per year. That means that more than 1 in every 8 Norwegian men will be diagnosed with the disease during their lifetime. Prostate cancer is responsible for the second highest number of cancer deaths in the country, only after lung cancer. In 2012 alone, 1006 Norwegian men lost their battle against prostate cancer (data from kreftregisteret).

Fortunately, being diagnosed with prostate cancer does not necessarily mean the end of it. In fact, most patients will survive without any form of treatment. They have a slow-growing cancer type with low risk of spreading to other organs. However, those patients with a more aggressive type require radical treatment, such as surgical resection of the prostate and the surrounding lymph nodes. To treat or not to treat, that’s the question. Unfortunately, the answer is not always clear. Today, medical imaging is playing an increasingly important role in helping urologists make the right decision.

Urologists base their decision of treatment (or not) on several criteria. First, they look at elevated levels of PSA, which is a blood marker for prostate cancer. Palpation gives them an impression of possible abnormalities in the prostate. Biopsy samples are subsequently taken from the prostate and tumor aggressiveness is reported by a pathologist. This is called tumor grading. Also, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is made to evaluate tumor involvement in the prostate and cancer spread to the surrounding lymph nodes and other organs. This evaluation, which is called staging, is performed by a radiologist. The current methods of tumor grading and staging, however, are not perfect. In unfortunate cases, misclassification can lead to unnecessary treatment of low-risk patients (over-treatment) or to failure to give adequate treatment to high-risk patients (under-treatment). In the MR Cancer Group at NTNU, we are developing advanced medical imaging methods for grading and staging of prostate cancer, to provide the medical team with better tools for clinical decision-making.

MRI is currently the imaging modality of choice for staging of prostate cancer, because of its versatility and excellent soft tissue contrast. Anatomical MR images provide the radiologist with information on tissue that looks suspicious, whereas functional MR images give information on tissue that behaves suspiciously. At St. Olavs Hospital, radiologists combine anatomical images with functional images that show changes in cell density and blood vasculature. Although it has been shown that staging based on this combination of images is more accurate than based on anatomical images alone, there is still enough room for improvement. For example, on the MR images it is relatively difficult to detect cancer spread to the lymph nodes and the bones. Positron emission tomography (PET) is an imaging technique that may be better suited for this task. We are currently investigating if the combination of PET and MRI can be used to improve staging in prostate cancer.

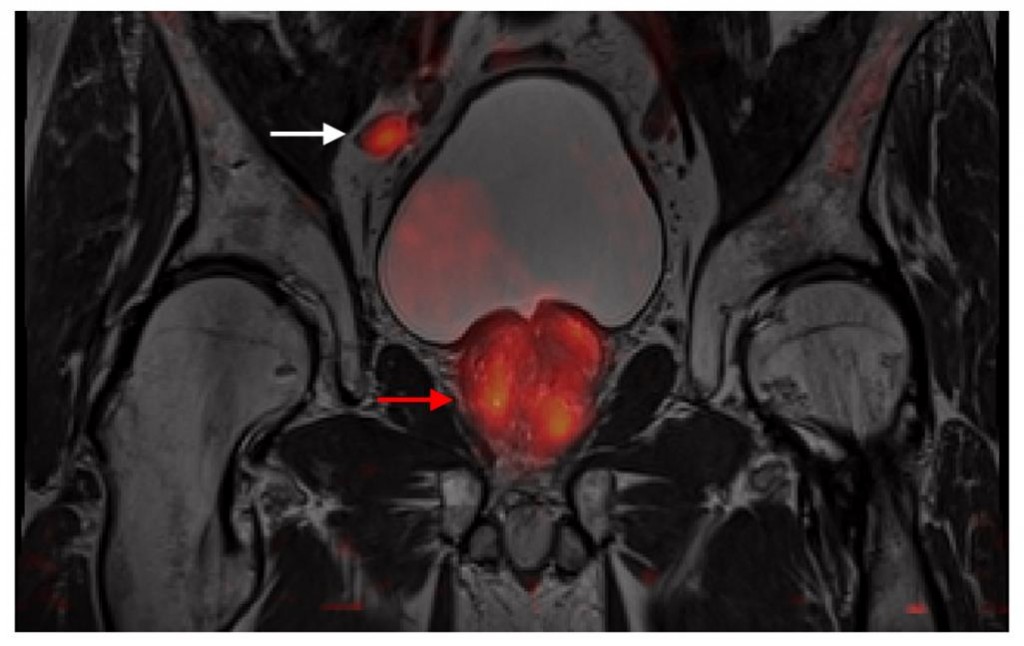

With PET, we make use of so-called tracer molecules to visualize cell metabolism. These tracer molecules, which are tagged with a radioactive label for detection, are injected in the blood stream of the patient. Which tracer molecule is used, depends on the metabolic process of interest. In a study that is currently running with financial support of the Norwegian Cancer Society, we are investigating PET imaging with a certain amino-acid analog (called FACBC). We know that prostate cancer cells metabolize more of this amino-acid than normal healthy cells do. So if we inject a patient with a small dose of these radio-labeled amino-acids, we expect them to end up mainly in the prostate cancer cells. As a consequence, tumors will light up as radioactive hot spots in the PET images (see figure 1).

Figure 1: An example of a PET image (in color), fused with the corresponding anatomical MR image (in gray). Accumulation of the radio-labeled amino-acids is clearly visible in a lymph node (white arrow) and the prostate (red arrow).

Up until now, 11 high-risk prostate cancer patients have been scanned with the new PET/MRI scanner at St. Olavs Hospital. The integrated design of this scanner enables acquisition of PET and MR images at the same time. With this ongoing study we hope to show that the combination of anatomical, functional and metabolic information from a single imaging session can improve staging of prostate cancer. In a future study, supported by the Movember Foundation, we want to investigate if we can also use PET/MRI for staging of initially treated patients for who recurrent disease is suspected. Another future possibility may be to use hybrid PET/MRI images for targeting of prostate biopsies. In combination with new MR-guided biopsy methods, which are currently under investigation by our group, this may increase the chances of having the most aggressive tissue available for tumor grading.

In summary, it may be clear that PET/MRI provides enough exciting opportunities to keep a researcher busy. Hopefully there is some time left to grow a moustache this month…

Curious why cancer cells have a different ‘diet’ than other cells? Check out this blog about hungry cancer cells (in Norwegian)