Blogger: Tonje Strømmen Steigedal

Blogger: Tonje Strømmen Steigedal

Our bodies constantly renew their cells. In healthy individuals this is tightly regulated so that old cells are removed at the same time as new ones are produced. Cancer arises when this regulation gets out of control due to, for example, mutations in the DNA. A tumour consisting of large numbers of cancer cells is formed.

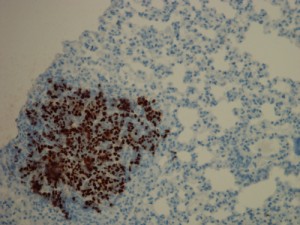

Lung tissue from mice: Healthy lung cells in blue with metastasis (cancer cells) shown in brown. (Photo: TS Steigedal)

In the environment around the cancer cells there are also many other types of cells that affect how the tumour develops. These cells are called stromal cells and include fibroblasts (connective tissue cells), macrophages (inflammation cells) and endothelium cells (blood vessel cells). Cancer cells can programme the stromal cells to their advantage so that the cancer cells get even better growing conditions.

In addition to cancer cells and stromal cells, there are also many other molecular components in the tumour’s microenvironment. Examples of such proteins include growth factors that stimulate cell division and cytokines that regulate inflammation reactions. In addition there are also large scaffold proteins outside the cells ensuring structure and support to all cells. Without such framework proteins the body would just be a random heap of different types of cells. This type of scaffold is called an extracellular matrix.

Exploiting the environment

Cancer cells exploit the other cells and proteins in the tumour microenvironment to their advantage so that the tumour can grow, divide and eventually spread (metastasise) to other organs. More and more attention is now given to the mapping and understanding of the tumour microenvironment’s composition in connection with cancer development.

Much speaks for the makeup of the tumour microenvironment playing a decisive role in how tumours develop and whether they spread. And perhaps this information could say something about how the tumour will respond to treatment. We now work on characterising tumours’ microenvironment and the goal is to understand how the composition of the microenvironment affects cancer development.

We have used a mouse model of breast cancer which has been modified so that the mice develop breast cancer in a predictable manner. By analysing the tumour microenvironment’s composition in tumours from different stages of cancer, we can say something about how they change throughout the tumour development. We have used advanced methods to map the complete composition of proteins in the tumour microenvironment.

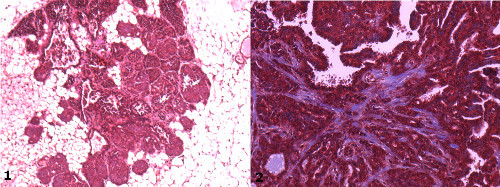

Tumour samples from modified mice models: 1) Low-grade tumour with few cancer cells (red) and very little visible ECM/collagen (blue). White areas are normal fat tissue. 2) Late-stage: invasive, aggressive tumour packed with cancer cells and lots of ECM/collagen. The tumour becomes fibrous and hard. (Photo: TS Steigedal).

New biomarkers for breast cancer?

We now see that some of these proteins also seem to appear in human breast cancer, and we wish to understand what function these proteins have. If we could understand what they mean to the cancer cells, we could perhaps use these proteins as new biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis, and the goal is also to identify new targets for treatment and therapy of breast cancer.