Bloger: Maria Ryssdal Kraby, PhD-Candidate, Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine

Breast cancer survival is high. However, many cancer survivors experience long-term side effects from treatment which impact their quality of life. For this reason, the Breast Cancer Subtypes Project studies a group of women we call Super survivors. They are so named because they survived breast cancer before today’s treatment options were available. If we can identify what characterises a Super survivor, we may have found a patient group which does not need all of the therapy they receive today.

This year, the Pink Ribbon campaign focuses on long-term effects: “Cancer-free, but not in good health. One in three women who survive breast cancer have long-term side effects from treatment.” It is important that the Pink Ribbon campaign highlights long-term effects, which impact the quality of life of so many people. One in 12 Norwegian women will develop breast cancer before turning 75 years of age. That corresponds 1784 of the seats at Lerkendal Stadium.

Luckily, breast cancer patients as a group have high survival rates. As many as 89.7% are alive 5 years after diagnosis. However, many of them must go through extensive treatment, often a combination of several treatment modalities. Breast cancer is treated with surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, antibodies and hormone therapy. Ninety percent are recommended hormone treatment and/or chemotherapy in addition to surgery. Side effects from breast cancer treatment include brittle bone disease, blood clots, hot flushes, hair loss, cardiovascular disease and neuropathy (tingling and reduced feeling in the hands and feet).

Breast cancer is not just one disease. Breast cancer is several, very different diseases which have differing biology and dissimilar survival.

There is an increasing focus on individualised treatment. That entails tailored therapy strategies for each patient, so that she receives the best treatment and follow-up for her breast cancer. Because breast cancer is not just one disease. Breast cancer is several, very different diseases which have differing biology and dissimilar survival.

Patients who have a disease with poor prognosis should have extensive therapy. But what about those that have a less aggressive form of breast cancer with a very good prognosis? How much therapy do they really need? In men with prostate cancer, there are some subgroups with such a good survival and such a low probability of disease spreading, that one chooses to refrain from treatment and follow the patient closely instead. Perhaps similar subgroups are to found in breast cancer, where removal of the tumour is sufficient?

Super survivors – What is it that separates them from others?

In the Breast Cancer Subtypes Group at NTNU, we study tissue samples from close to 2000 women from Trøndelag born between 1886 and 1977. About 900 of these were diagnosed with breast cancer before today’s treatment options were available. Even though most of them were only treated with surgery, several women lived long after they were diagnosed, and died from causes other than breast cancer. This could imply that they did not need any more than the limited treatment they received. We can call these women Super survivors. One of our goals is to identify them. What is it that separates them from others?

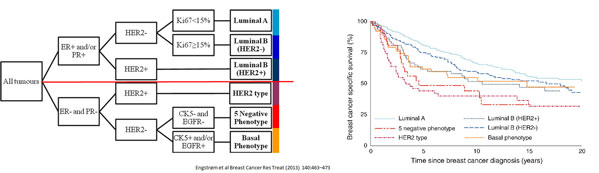

We search for the answer within the tumour. By examining proteins and genes in a tumour, it is possible to learn more about the woman’s prognosis and what kind of treatment would be most effective. Our research group has reclassified breast cancer tumours into 6 subgroups (subtypes) with differing biology and survival. Now, we want to study which proteins or genes in the tumour that can be used to determine the patient’s prognosis within each subtype. We call it a search for prognostic markers in the subtypes.

From Engstrøm et al. A: Classification algorithm to reclassify breast cancer tumours into subtypes. Oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), cytokeratin (CK5), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). B: Survival curves for breast cancer specific survival, divided by subtype. Best prognosis in Luminal A, and poorest prognosis in HER2 type.

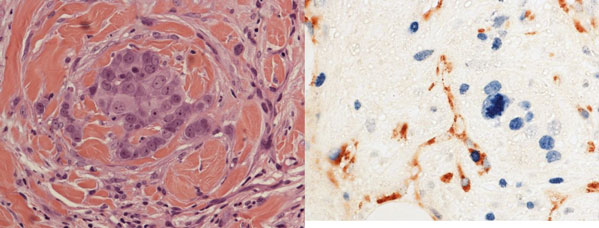

Without a blood supply, tumour size cannot exceed 1-3mm3. For this reason, cancer cells stimulate nearby blood vessels to grow into the tumour, so that it can become larger and spread within the body. To find out more about the biology of each subtype, and to find out whether the amount of blood vessels could have prognostic value, I have counted blood vessels in breast cancer tumours.

We compared blood vessels in the subtype with the best prognosis, Luminal A, to a subtype with a much poorer prognosis called the Basal Phenotype (BP). In order to see the blood vessels, we used immunohistochemistry, a method that visualises specific proteins in the tumour. Then, using a microscope, I counted the number of blood vessels in total, and the number of growing blood vessels. For Luminal A, patients with few blood vessels in their tumour had a better survival than those with many blood vessels. For the BP, the number of blood vessels had no influence on survival.

This supports the hypothesis that there are different prognostic markers for each subtype. Whether the amount of blood vessels provides prognostic information in the Luminal A subtype, must be confirmed in a study with a larger sample size. If our findings persist, the number of vessels in Luminal A tumours might add new information that could aid in the identification of Super survivors.

Photo: AM Bofin and MR Kraby. A: Tissue sample from tumour stained with haematoxylin, eosin and saffron. B: Tissue sample stained with immunohistochemistry so that blood vessels become brown and cells in proliferation become blue.

The Breast Cancer Subtypes Project is made possible through financial support from the Norwegian Cancer Society, the Research Council of Norway, the Central Norway Regional Health Authority, Kreftfondet at St. Olavs University Hospital and the legacy of Rakel og Otto Kr. Bruun.