Blogger: Anja Johansen,

phd student, Faculty of Humanities

Some weeks ago I visited the exhibition ‘Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age’, at FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) in Liverpool. FACT is one of an increasing number of foundations in the UK and abroad that aim to foster collaboration and innovation across the creative industries, health, higher education and arts sectors in order to ‘develop multi-disciplinary projects exploring the relationship between technology and culture’.

Group Therapy: Mental Distress in a Digital Age

FACT, Liverpool, UK

March 6 – May 17 2015

Curated by Vanessa Bartlett and Mike Stubbs

For this last exhibition curator Vanessa Bartlett and FACT Director Mike Stubbs have worked closely with Mersey Care NHS Trust and other health institutions in the UK, to present a diverse collection of artworks, research projects and design innovations exploring the connection between mental health, technology and society.

It is widely acknowledged that art and aesthetic experiences, like visual arts, music, theatre or the appreciation of nature, can have a positive impact on peoples’ lives and contribute to feelings of pleasure, joy and wellbeing. Especially in times of mental distress, depression and disease art, poetry and music can provide comfort, and be an important means of expression and reworking of difficult emotions.

Recently, mental health facilities, hospitals and treatment centres have also taken this into consideration. At St.Olav’s hospital architecture and art are consciously designed as an integrated part of the university clinic treatment setting, including secluded gardens, colourful murals and decorative sculptural objects – as part of the project Visual vitamins. The hospital has the largest public art collection in Norway outside the art institutions, with 2,000 works of art distributed over more than 200,000 square meters.

While art is often given such a therapeutic role, this is not the only way that art and artist can contribute to questions about health, illness and wellbeing. As part of the exhibition Group Therapy, artists have collaborated with scientist, engineers, patient groups and designers to explore and develop novel interfaces for getting in touch with our bodily and mental selves – and the surrounding world.

Distress in a digital age

As stated by the curators, digital technologies can be seen as both a problem and the solution to mental health issues today:

‘For many, the presence of digital technologies is exasperating this problem [ie. mental distress] by altering our sense of self and our social relationships. Meanwhile, others suggest that technological innovation is a crucial tool for finding new ways to improve the lives of those who experience social isolation, illness and emotional distress.’

Framing mental health as ‘a social issue that can affect all of our lives’, the exhibition included several works that aimed to make visitors reflect on their own bodily and mental states. Some works, like the machine-generated prescriptions offered in the digital questionnaire by Ubermorgen, or the therapeutic guidance in the video The Financial Crisis by the artist group Superflex, provided a playful yet critical comment to the cultural desire for quick fixes to complex emotional problems. Other projects documented historical and contemporary approaches to mental health and therapy through film and photography, while some were also developed in collaboration with patients groups and community members to provide reflection on and practical solutions to everyday problems.

Group Therapy: Let’s work together

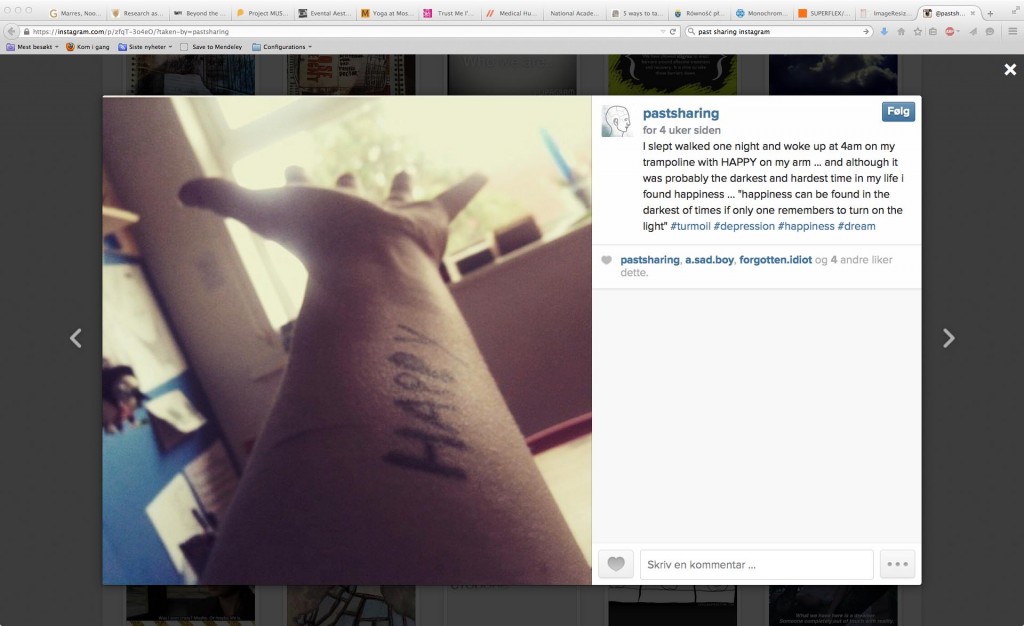

Past sharing is a collective effort co-produced by artist Erica Scourti and a group of 13- 18 year olds through FACT’s young people’s programme Freehand. The programme is designed to support young people to develop skills in a range of areas including filmmaking, management, and digital art and design. With Scourti the youngsters explored their own relationship with the Internet and its impact on their mental health through a series of workshops, and a collective Instagram account for sharing thoughts, poetry and imagery related to the topic. The content has been created, tagged and commented on anonymously.

Let’s talk about it. Screenshot from the Instagram account #pastsharing by Erica Scourti and Freehand members at FACT.

Several of the artistic contributions reflect personal experiences with mental distress or illness, either self-experienced or within the near family. Collaboration is taken even a step further in Madlove; a project that invites people to discuss and design their ideal asylum, imagined as a ‘safe place to go mad’. The project is initiated by the artist vacuum cleaner and Hannah Hull in collaboration with architects James Christian and Benjamin Koslowski. Located at the ground floor of the gallery this space will provide a spatial and social arena for exploring madness throughout the exhibition period, and will function as a proposal for designing mental health hospitals. Past and future events are documented through the exhibition blog.

As part of the programme the exhibition offers several events and workshops related to the topic of health, art and wellbeing. When I was there I participated in a free yoga session led by Neeta Madahar, aimed at providing us with techniques for bodily awareness and relaxation. Madahar has also made an animation for the show at FACT together with Kate Owens. Me and the Black Dog refers to depression through a metaphorical narrative, and argues for the need to get more in touch with the darker side of our personality.

Depression is a black dog. Still from the animation Me and the black dog, by Neeta Madahar and Kate Owens.

Art and science: Sensory experience at the interface

We all have our grey days. But some of us struggle with more severe forms of mental illness that makes it hard to function socially. Without having experienced it ourselves, is there any way of understanding what it feels like to be severely mentally ill, even psychotic? During the 1970s some researchers experimented with LSD in order to get an idea of what it felt like for mentally ill to experience hallucination. Artist and researcher Jennifer Kanary Nikolov(a), on her side, attempts to facilitate empathy and understanding through digital means.

Dazed and confused. The author trying out Jennifer Kanary Nikolov(a)’s do-it-yourself psychosis kit. Photo: Rob Heron

Labyrinth Psychotica is a project that includes a physical labyrinth and a wearable. device. The wearable is described as an ‘interactive augmented reality cinema walk that functions as a do-it-yourself-psychosis-kit’. Participants are invited to take the perspective of an imagined person experiencing moments of psychosis, and are guided by voices and directions in a 20 min session. The kit blends perceptual reality and audio-visual hallucinations, which makes otherwise ordinary and safe surroundings seem frightening and unreliable. I can confess it was an intensely discomforting experience that would have been hard to imagine. As such, the project provided a striking example of the importance of bodily, subjective experience in understanding mental illness, which is still missing in mental health education and treatment today.

The Heart Library Project by George P. Khut is also based on interactive interfaces for the audience to explore on site, but provided a more soothing, therapeutic environment. In hospitals, patients’ bodies are rendered as graphs and numbers, and the authority in providing knowledge about the body and its malfunctions is handed over to doctors and machines. Through his project Khut wanted to provide patients with another way of relating to their bodies, and to regain a sense of agency and wonder over their bodies.

The interactive installation is based on a biofeedback interface, measuring the participants heart rate through a sensor attached to the ear or finger and translating it into fluctuating, colourful blobs, projected on a screen in the ceiling above. Participants are invited to lie down on a bench, and encouraged to try to alter the imagery by relaxing and pacing down the breath.

Visual feedback. The Heart Library by George P. Khut, installation shot at FACT. Photo by Anja Johansen.

As part of the process, Khut also invites participants to share their experience through the medium of drawing, providing a colourful archive of peoples ‘body portraits’ hung on the walls. Similar forms of body mappings have recently been tested with good results in consultation with chronic pain patients.

The projects presented in the exhibition Group Therapy provide insights into how artists, in collaboration with scientist, designers and community groups, can make important contributions to innovations in the health and medicine sector. These issues are too important to be left alone. Let’s work together!