Blogger: Siver A. Moestue

One of the best things about being a researcher is that you can work on completely new ideas and concepts without giving much thought to what is actually possible or not. Often it turns out that what you thought was impossible is possible after all if you a) develop a new technology, b) let enough researchers work on it for long enough, or c) have a bit of luck. Preferably all three.

One of the areas where we are still at the starting line is nanomedicine. Even though we are capable of making particles at nanoscale today, we know little about what role they will play in tomorrow’s medicine. In the meantime we can enjoy ourselves with hatching clever, and less clever, ideas and evaluate how far they could contribute to improved treatments in the future.

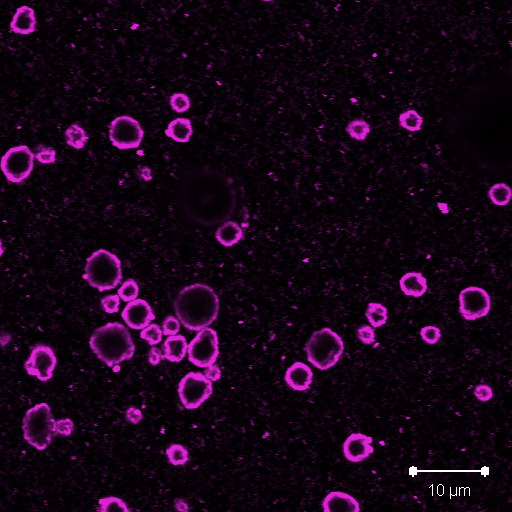

This is the status at NTNU today: In cooperation with SINTEF, we can under controlled conditions produce particles with a diameter of a few hundred nanometres (which is about as much as your fingernails grow while you read this…). These particles are made from the same plastic materials that are used in superglue. But at SINTEF they let the glue “dry” in such a way that we maintain a whole different level of control over shape, size and characteristics, than if you glue a broken cup together. In this way they produce tiny little plastic particles. They can also put things inside them or decorate them with all sorts on the outside. If you place them in water together with some proteins and give them a shake, they can even join up and produce air-filled bubbles.

You can read more about nanotechnology at SINTEF here.

Nanoparticles can be used for many things. At NTNU there are now about 20 researchers looking into how these tiny superglue particles can be used to improve cancer treatment. And so some of us privileged researchers are allowed to be creative.

Could we use these particles to detect cancer? Perhaps by placing a contrast agent inside and decorating the outside with something that recognises cancer cells? Or could it perhaps be smarter to use them to treat cancer? One of the problems with breast cancer treatment is that patients have to stop chemotherapy due to side effects. But if we could make sure that more chemo ends up in the tumour and less ends up in places where it causes side effects, this problem could largely be solved.

Researchers at NTNU, for example, work on filling the superglue droplets with chemo, making them into ‘large’ bubbles (about as much as a fingernail grows in an hour…), so that the superglue-droplet chemo can safely be transported around in the blood stream. And here comes the great trick: By targeting the superglue-droplet chemo-bubbles with ultrasound waves, we could make them burst where we want them to (for example in a tumour) so that the chemotherapy is released just there and nowhere else. This sounds difficult, but NTNU has for many years been a world leader in ultrasound technology. If we gain control over the behaviour of the nanoparticles, this should absolutely be possible.

Finally, my own personal dream for the future: Nanoparticles containing chemo which are decorated with 1) structures that recognise cancer cells, and 2) structures making them ‘invisible’ to the body. Such particles could circulate in the blood over longer periods of time, acting as secret agents. When they find a unsuspecting cancer cell in the blood stream, they can attach themselves and deliver a suitable dose of chemo. The application? Well, you could imagine that such particles could help prevent a relapse in breast cancer patients after surgery, because often there will remain a few cancerous cells in the body that could cause a relapse several years after an operation.

Is any of this possible? 10 years ago many would have said a resounding “NO”, but now we can stretch to a “perhaps” or “why not”. The research area is growing, both at NTNU and in other places, thanks to research funding from, for example, the Norwegian Cancer Society and the Research Council of Norway. There is a steep learning curve, and we learn something new about these particles literally every day – a dream existence for a researcher.